Stanley Park in Vancouver is one of the most renowned urban parks in the world, attracting visitors from all over the globe.

Stanley Park in Vancouver is one of the most renowned urban parks in the world, attracting visitors from all over the globe.

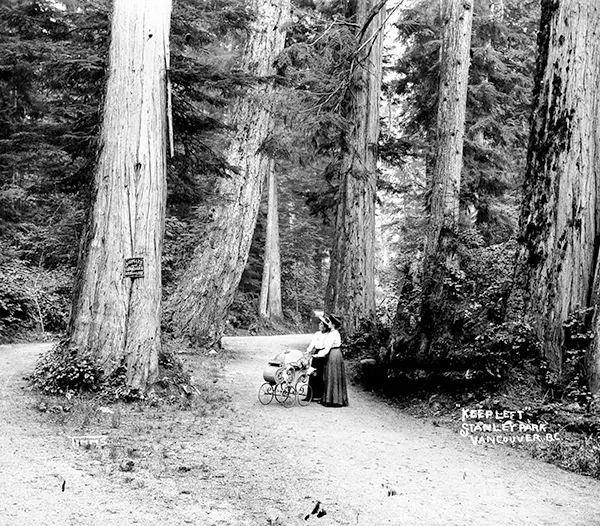

With its lush forests, stunning views, and diverse wildlife, the park has become a beloved landmark of the city. This article shows old photos of Stanley Park, providing an unprecedented glimpse into the park’s history.

Stanley Park has a long history. The land was originally used by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years before British Columbia was colonized by the British during the 1858 Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and was one of the first areas to be explored in the city.

For many years after colonization, the future park with its abundant resources would also be home to non-Indigenous settlers. The land was later turned into Vancouver’s first park when the city incorporated in 1886.

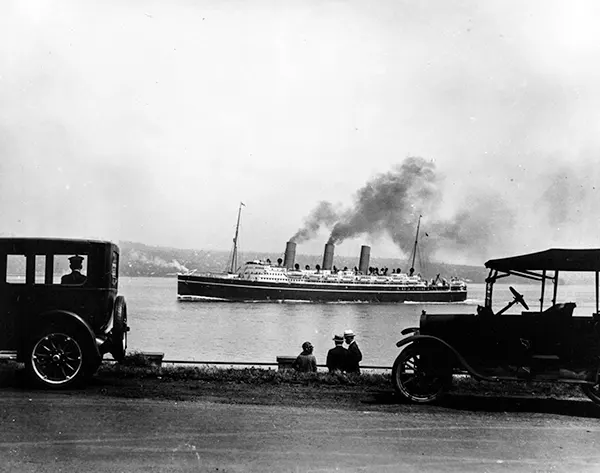

It was named after Lord Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby, a British politician who had recently been appointed Governor General. It was originally known as Coal Peninsula and was set aside for military fortifications to guard the entrance to Vancouver harbor.

In 1886 Vancouver city council successfully sought a lease of the park which was granted for $1 per year. In September 1888 Lord Stanley opened the park in his name. Unlike other large urban parks, Stanley Park is not the creation of a landscape architect, but rather the evolution of a forest and urban space over many years.

Unlike other large urban parks, Stanley Park is not the creation of a landscape architect, but rather the evolution of a forest and urban space over many years.

Most of the manmade structures present in the park were built between 1911 and 1937 under the influence of then superintendent W.S. Rawlings. Additional attractions, such as a polar bear exhibit, aquarium, and a miniature train, were added in the post-war period.

Much of the park remains as densely forested as it was in the late 1800s, with about a half million trees, some of which stand as tall as 76 meters (249 ft) and are hundreds of years old.

Thousands of trees were lost (and many replanted) after three major windstorms that took place in the past 100 years, the last in 2006.

Construction of the 8.8-kilometer (5.5 mi) seawall and walkway around the park began in 1917 and took several decades to complete.

Construction of the 8.8-kilometer (5.5 mi) seawall and walkway around the park began in 1917 and took several decades to complete.

The original idea for the seawall is attributed to park board superintendent, W. S. Rawlings, who conveyed his vision in 1918:

It is not difficult to imagine what the realization of such an undertaking would mean to the attractions of the park and personally I doubt if there exists anywhere on this continent such possibilities of a combined park and marine walk as we have in Stanley Park.

James “Jimmy” Cunningham, a master mason, dedicated 32 years of his life to the construction of the seawall from 1931 until his retirement in 1963. Cunningham continued to return to monitor the wall’s progress until his death at 85.

The walkway has been extended several times and is currently 22 kilometers (14 mi) from end to end, making it the world’s longest uninterrupted waterfront walkway.

The walkway has been extended several times and is currently 22 kilometers (14 mi) from end to end, making it the world’s longest uninterrupted waterfront walkway.

The Stanley Park portion is just under half of the entire length, which starts at Canada Place in the downtown core, runs around Stanley Park, along English Bay, around False Creek, and finally to Kitsilano Beach.

From there, a trail continues 600 meters to the west, connecting to an additional 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) of beaches and pathways which terminate at the mouth of the Fraser River. Violent windstorms have struck Stanley Park and felled many of its trees numerous times in the past. Between 1900 and 1960, nineteen separate windstorms swept through the park, causing significant damage to the forest cover.

Violent windstorms have struck Stanley Park and felled many of its trees numerous times in the past. Between 1900 and 1960, nineteen separate windstorms swept through the park, causing significant damage to the forest cover.

The park lost some of its oldest trees through major storms twice in the last century and then again in 2006. The first was a combination of an October windstorm in 1934 and a subsequent snowstorm the following January that felled thousands of trees, primarily between Beaver Lake and Prospect Point.

Another storm in October 1962, the remnants of Typhoon Freda, cleared a 2.4-hectare (6-acre) virgin tract behind the children’s zoo, which opened an area for a new miniature railway that replaced a smaller version built in the 1940s. In total, approximately 3,000 trees were lost in that storm.

One stand of tall trees in the center of the park did not survive beyond the 1960s after becoming a popular tourist attraction.

The “Seven Sisters” are memorialized by a plaque and young replacement trees in the same location along Lovers Walk, a forest trail that connects Beaver Lake with Second Beach. “They were so popular that people basically killed them by walking on their roots,” says historian John Atkin.