At Citrus High School in California, honor student Judy Fay worked on the blackboard during an English class.

By the 1970s teenage pregnancies were recognized as a problem worldwide. The continuing apprehension about teenage pregnancy was based on the profound impact that teenage pregnancy could have on the lives of the girls and their children.

Demographic studies reported that in developed countries such as the United States, teenage pregnancy results in lower educational attainment, increased rates of poverty, and worse “life outcomes” for children of teenage mothers compared to children of young adult women.

The pictures shown in this article chronicled the day-to-day lives of teen moms and moms-to-be in the typical southern California town of Azusa in 1971. It was originally published as a cover story in Life magazine and it was titled “Help for High School Mothers”.

“In a public high school classroom [the article began], a 16-year-old student, eight months pregnant and unmarried, presents a book report. Her classmates and teacher are unruffled, for the quiet scene is an everyday event at Citrus High in Azusa, Calif., and elsewhere around the country where educators are taking radical new approaches to an old and painful problem.

Until a few years ago, the nation’s public schools dealt with teenage pregnancies by expelling the girls or by putting pressure on them to leave. Many humiliated families arranged secret and illegal abortions for their daughters. Others sent them away to “visit relatives” or, if they could afford it, hid them in private nursing homes.

“Today the attitude toward high school mothers is changing dramatically. While teenage pregnancy is just as unwanted and undesirable as ever, more and more parents and schools are trying to help the girls put their lives together again instead of ostracizing them.

In nearly every major city programs now exist to meet the special educational, medical, and psychological needs of teen-age mothers. In almost every case the programs have won strong community support. . . . Many communities provide medical clinics and counseling for the new mothers who will number an estimated 200,000 this year.”

“[That said], there are still not enough programs in the country. A recent study concludes that 75 percent of pregnant teen-agers drop out of school. But more and more girls are making the tough decisions to stay in school, for their own good and for the future of their babies.”

A few weeks after the story ran, the letters to the editor published in Life magazine in response to the story were mostly negative, along the lines of one from a reader in Colorado, who wrote that “the April 2 cover sets some sort of new dimension of achievement in crass, lurid, inelegant journalistic bad taste.

To proffer a picture of this pathetic schoolchild with her grotesque maternity figure over the bold type ‘High School Pregnancy’ simply makes a bad, sad scene.”

Linda Twardowski, a recent Citrus graduate, explained the basics of diaper-changing in a childcare class, using her son Charles. The girls also were taught prenatal care, cooking, and budgeting.

Lupe Enriquez, 17, took notes on nutrition in homemaking class and received a playful pat from another expectant mother, Lynda Kump. Like several of the girls in the maternity program at Citrus, Lupe got married after learning she was pregnant.

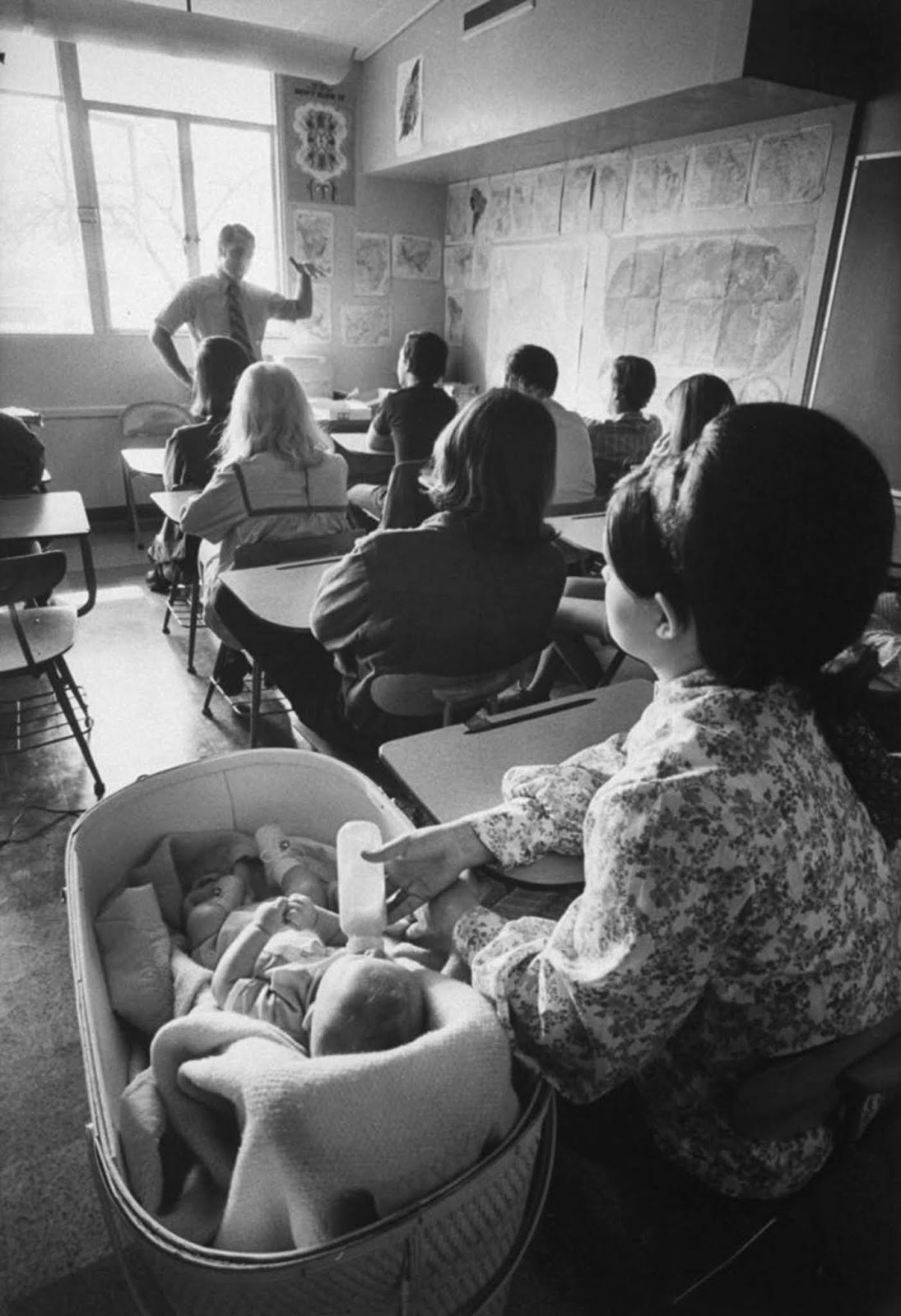

Cheryl Gue, 17, quieted her son Michael with a bottle. Although the sound of crying babies was a normal disruption at Citrus, the more vocal ones were usually hustled out of class. The school was equipped with playpens, cribs, and toys. The mothers were required to come to school for the morning child-care courses but could study academic subjects at home.

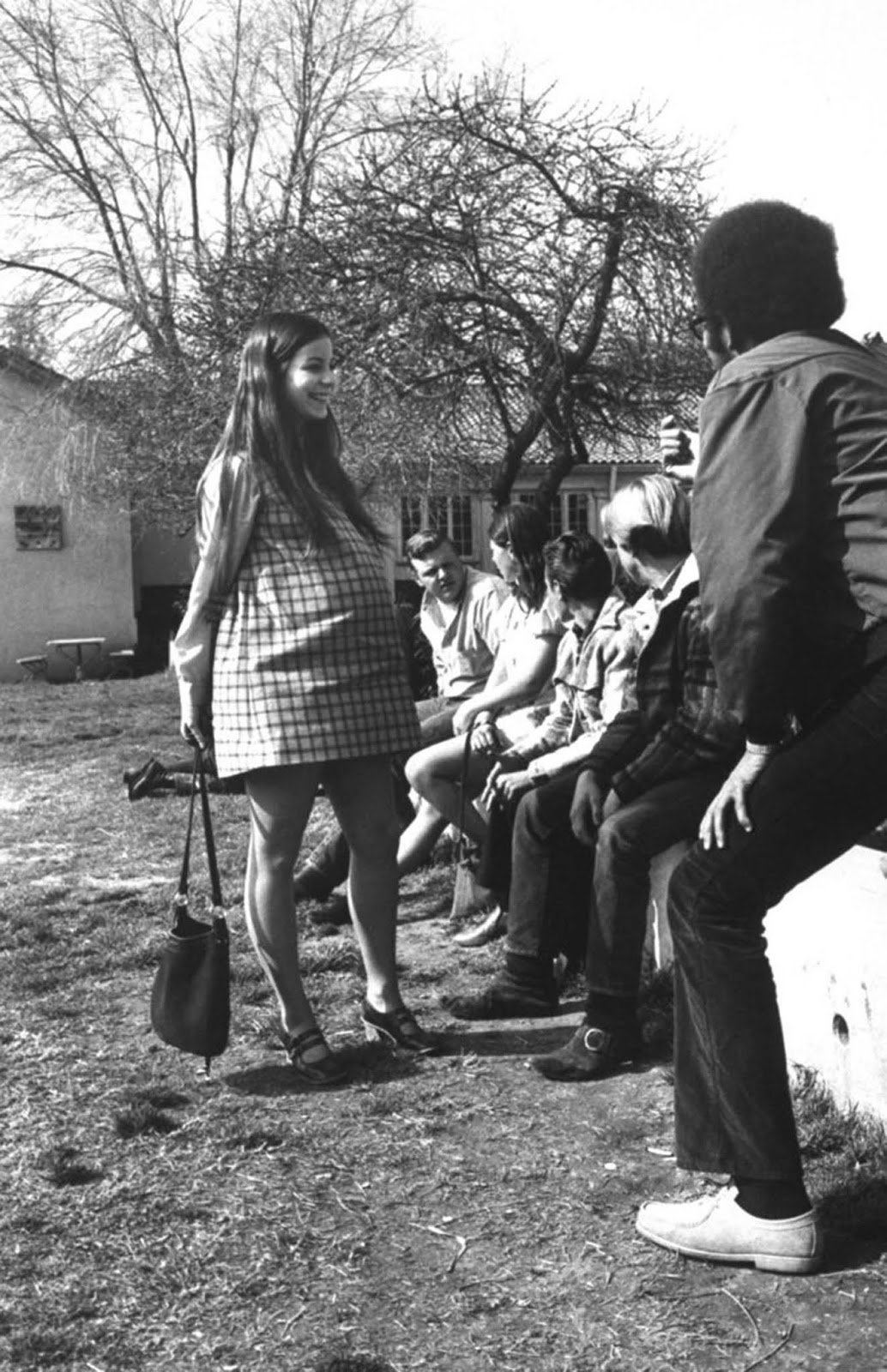

Pregnant high schoolers, Azusa, Calif., 1971.

High school students with babies, Azusa, Calif., 1971.

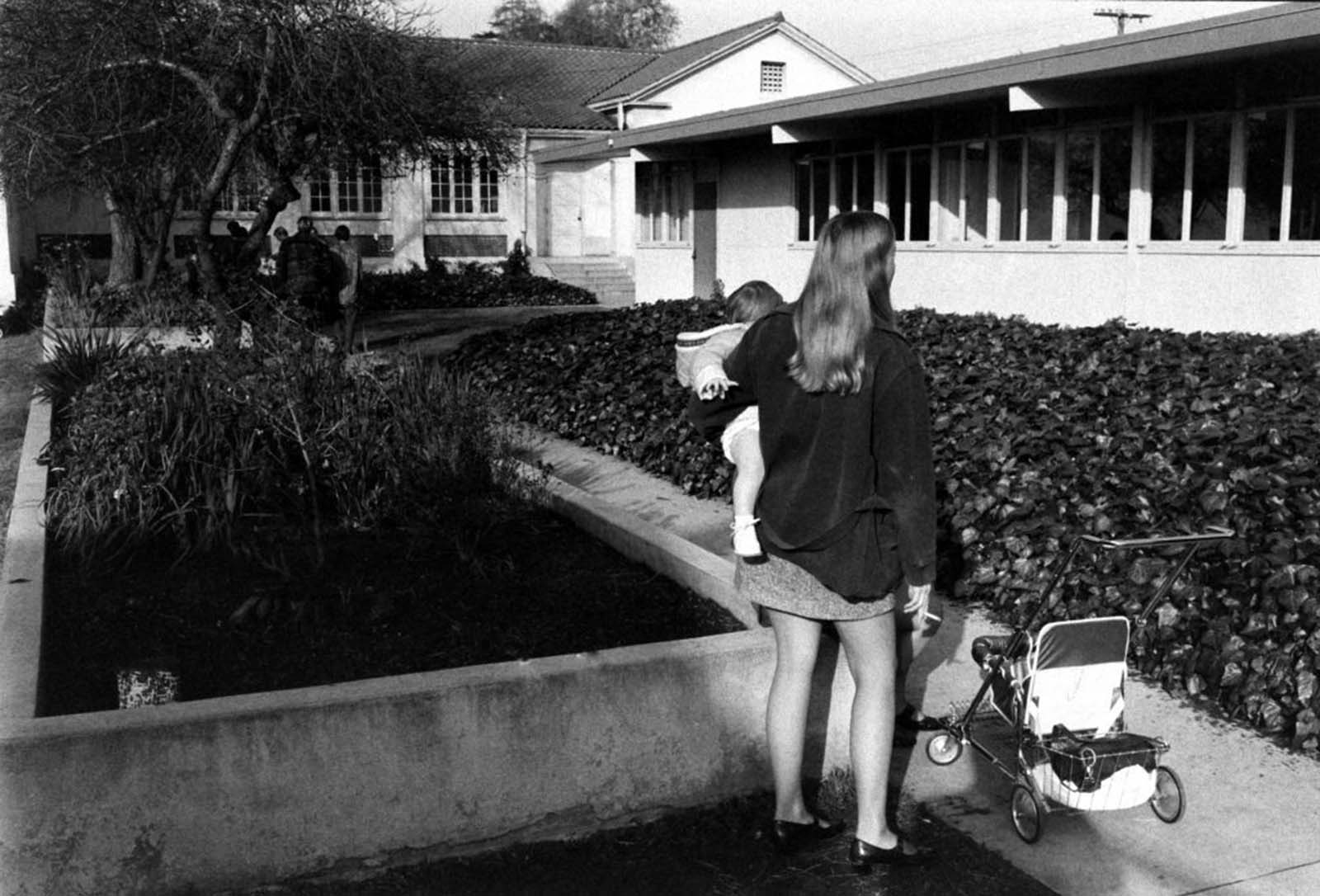

Vicki Conger, 17, with her 13-month-old daughter, Shawn Michelle, Azusa, Calif. 1971.

Sandy Winters, 13, who recently enrolled at Citrus, talked about her courses with principal James Georgeou, founder of the program for young mothers.

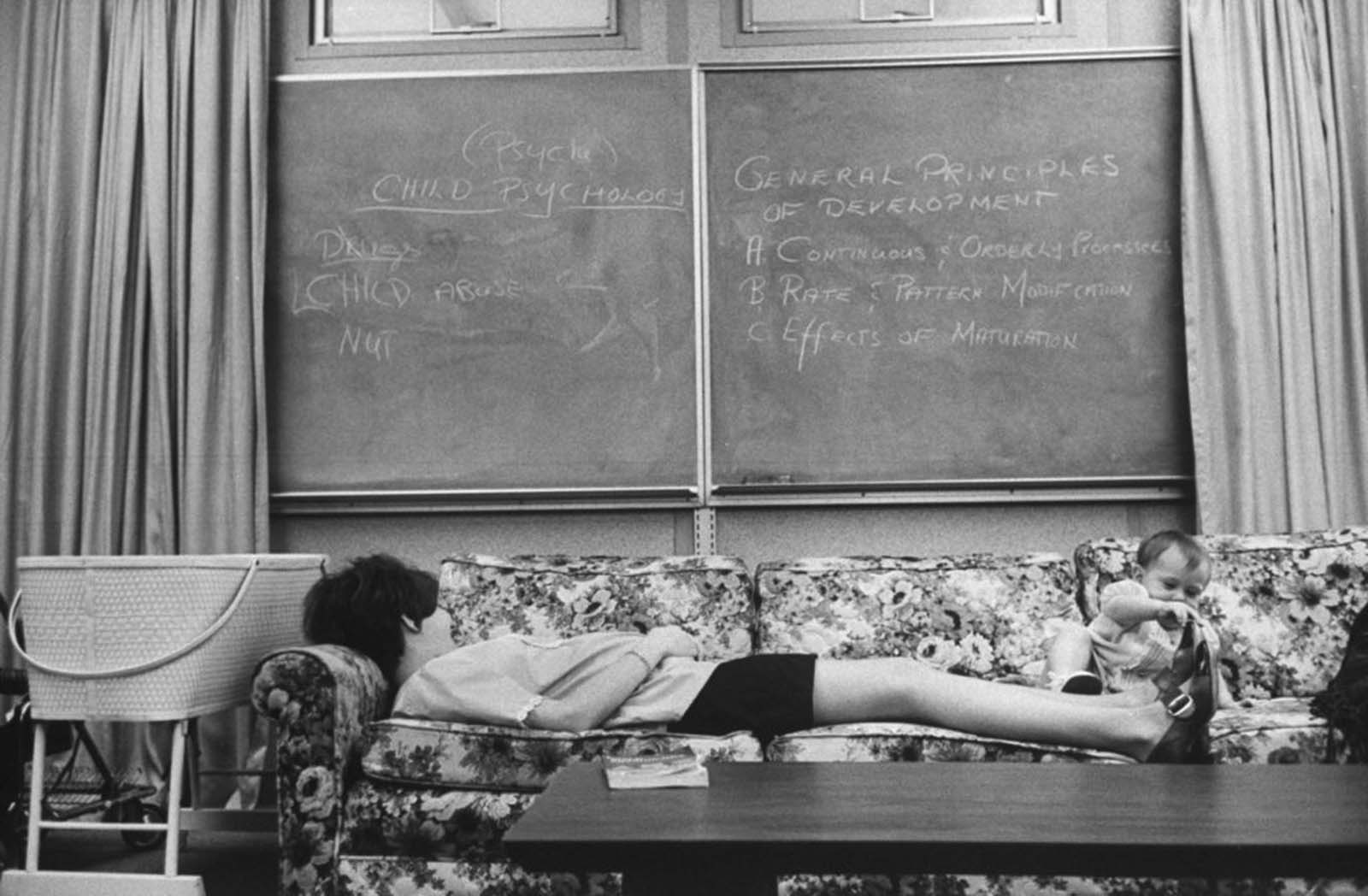

Expectant mothers were allowed to take naps in homemaking class. Here Lori Cardin, 17 and six months pregnant tried to catch 40 winks despite playful attention from young Shawn Conger.

In the courtyard outside the school, Vicki Conger, 17, took a stroll with her 13-month-old daughter, Shawn Michelle.

Judy Fay chatted with a group of students outside class. With pregnant girls at Citrus, the boys cleaned up their language and courteously held open doors, and even pushed strollers.

Toward the end of her pregnancy, Judy Fay’s father, an aerospace worker, drove her to and from school each day.

Judy’s parents, Henry and Luella Fay, found to their relief that the neighbors were sympathetic to Judy’s plight. “We have had a lot of compliments because of the way we faced up to the problem,” said Mrs. Fay.

In the canopied bed where she had slept since childhood, Judy cuddled her son Dylan. “My son may have been unplanned,” Judy said, “but he is not unloved.”